Medieval people called the catastrophe of the 14th century either the "Great Pestilence"' or the "Great Plague." Writers contemporary to the plague referred to the event as the "Great Mortality." Swedish and Danish chronicles of the 16th century described the events as "black" for the first time, likely to refer to black as glum or dreadful denoting the terror of the events. The German physician Justus Hecker suggested that a mistranslation of the Latin atra mors (terrible, or black, death) had occurred in Scandinavia when he described "The Black Death in the 14th century." Black Death became more widely used in the German- and English-speaking worlds.

In October 1347, a ship came from the Crimea and Asia and docked in Messina, Sicily. Aboard the ship were not only sailors but rats. The rats brought with them the Black Death, the bubonic plague. Reports that came to Europe about the disease indicated that 20 million people had died in Asia. Knowing what happened in Europe, this was probably an underestimate, because there were more people in Asia than Europe. Best estimates now are that at least 25 million people died in Europe from 1347 to 1352. This was almost 40% of the population (some estimates indicate 60%). Half of Paris's population of 100,000 people died. In Italy, Florence's population was reduced from 120,000 inhabitants in 1338 to 50,000 in 1351. The plague was a disaster practically unequalled in the annals of recorded history and it took 150 years for Europe�s population to recover.

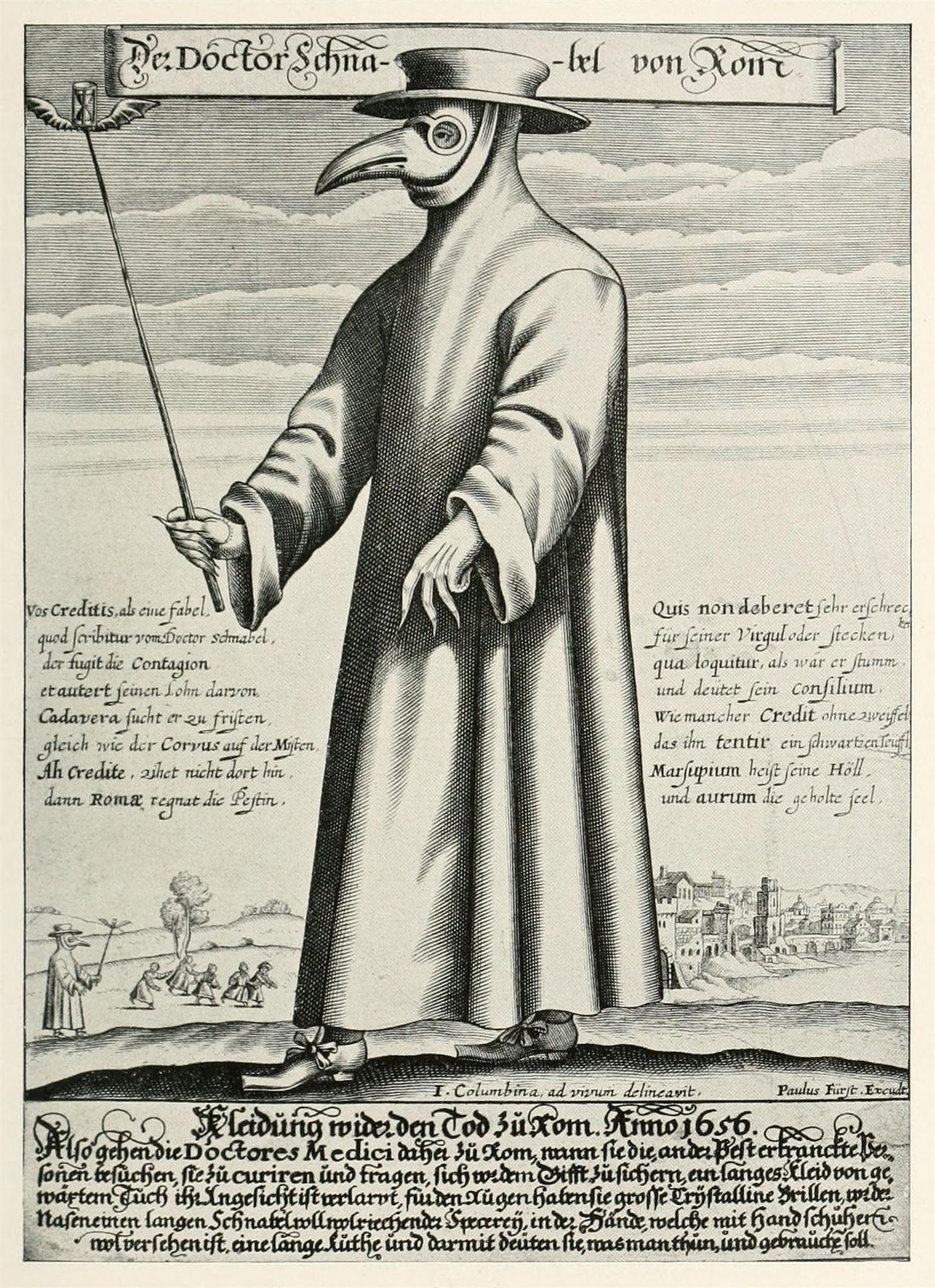

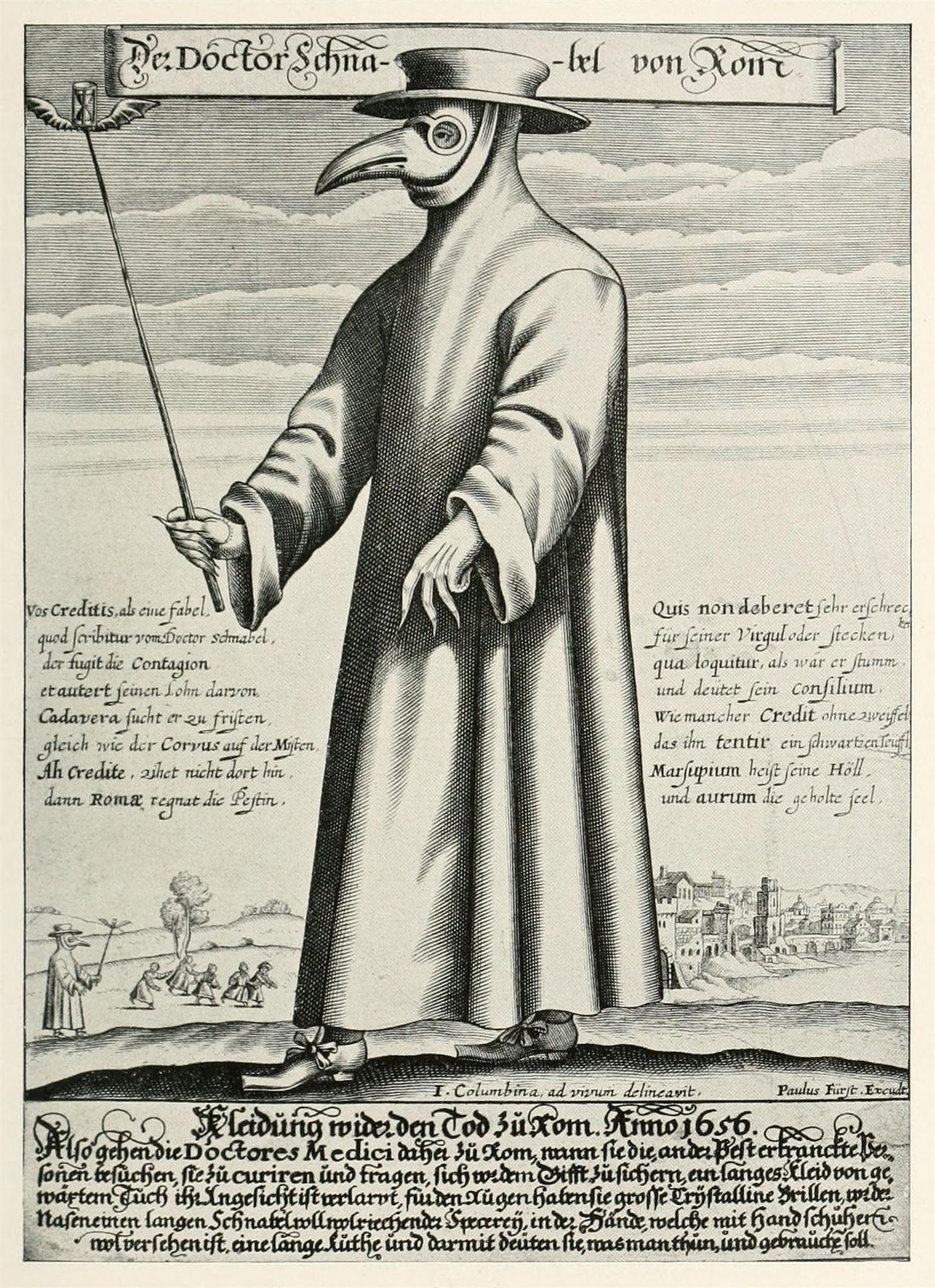

The plague doctor costume consisted of an ankle length overcoat, a bird-like beak mask filled with sweet or strong smelling substances, along with gloves and boots. The mask had glass openings for the eyes. Straps held the beak in front of the doctor's nose which had two small nose holes and was a type of respirator. The beak could hold dried flowers (e.g roses or carnations), herbs (e.g. mint), spices, camphor or a vinegar sponge. The purpose of the mask was to remove bad smells, thought to be the principal cause of the disease. Doctors believed the herbs would counter the "evil" smells of the plague and prevent them from becoming infected. The costume included a wide brimmed leather hat to indicate their profession. They used wooden canes to point out areas needing attention and to examine patients without touching them. The canes were also used to keep people away and to remove clothing from plague victims without having to touch them.

The bubonic plague mechanism was dependent on two populations of rodents: one resistant to the disease, which acts as hosts, keeping the disease endemic; and a second that lacks resistance. When the second population dies, the fleas move on to other hosts, including people, thus creating a human epidemic. The original carrier for the plague-infected fleas thought to be responsible for the Black Death was the black rat. The bacterium responsible for the Black Death, Yersinia pestis, was commonly endemic in only a few rodent species and is usually transmitted zoonotically by the rat flea. Brown rats may suffer from plague, as can many non-rodent species, including dogs, cats, and humans.

The burning of Jews in the 14th century during the black death (bubonic plague). Jews were perceived as being less susceptible to the plague than their neighbours (likely the result of Jewish ritual regarding personal hygiene) and they were accused of poisoning Christian wells: thought to be the source of the plague.

Page CCXXX, English Translation:

"The miserable wretched Jews, in A.D. 1337, at Deckendorf, on the Danube, in Bavaria, in scorn and ignominy of the divine majesty and high veneration paid to our Lord Jesus Christ and to the holy Christian religion, stabbed the Holy Sacrament many times. They then threw it into a hot oven, and as it remained unconsumed, they finally placed it on an anvil and struck it with hammers. When this became known, the Jews were seized by Hartmann von Degenberg, the caretaker, and the citizens; and when the truth was established, they were deservedly condemned to death. And this same Host, being present at the Holy Sepulchre, is venerated for its many miracles.

Thereafter, in the year A.D. 1348, all the Jews in Germany were burned, having been accused of poisoning the wells, as many of them confessed.

At this time locusts and vermin passed through the sky from east to west like a thick cloud, devastating all vegetation and fruits; and after they were dispersed the stench caused a horrible pestilence.

A pitiful and lamentable pestilence began in the year 1348 and endured for three years throughout the world. It resulted from the aforesaid locusts or vermin. It started in India and spread as far as England, ravaging Italy and France, and finally Germany and Hungary. The mortality was so rapid and great that barely ten persons out of every thousand survived. In some regions only about one third of the population escaped. Many cities, towns, marts and villages died out entirely and remained void. Some said that the Jews increased this calamity by poisoning the wells."

Page CCLXIIII, English Translation:

"Nothing is better than death, nothing is worse than an unjust life.

Death, the best for men, the everlasting rest from labors,

You loosen the yoke of old age by the will of God,

You remove the heavy chains from the neck of those held captive,

And you take away exile. You break open prison doors.

You snatch away the unworthy, making possessions equal in fair portions,

And you remain unmoved, incapable of being persuaded by any means.

Set in place since the first day, you order the soul to

Bear all things serenely with the promise of an end to labors.

Without you life is torment and an everlasting prison."

©2017 John Martin Rare Book Room, Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, 600 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242-1098

Image: Pieter Bruegel, The Triumph of Death (detail), c. 1562, oil on panel, 117 x 162 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Acknowledgements to Alice M. Phillips for her work editing the original exhibit material and subsequent web design.

The nearly 6,500 volumes in the John Martin Rare Book Room are original works representing classic contributions to the history of the health sciences from the 15th through 21st Centuries. Also included are selected books, reprints, and journals dealing with the history of medicine at the University and in the State of Iowa.